Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2025

Lo Brutto Stahl, Paris & Basel

Exhibition Text

2024

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

DUVE, Berlin

Exhibition Text

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

Incubator, London

Exhibition Text

2023

QUEERCIRCLE, London

Exhibition Text

2023

L.U.P.O., Milan

Catalogue Essay

2023

'To be one human creature is to be a legion of mannequins,'[1] proclaims the horned goddess of Leonora Carrington’s little-known short story, ‘My Mother’s a Cow’. I would be lying if I told you I understood much of the overtly surreal and imaginative cosmology that Carrington conjures in this story – a quasi-religious dialogue between a daughter and Holy Mother that problematises assumptions of the masculine in Christian theology. It is nevertheless a marvellous and incendiary tale, gesturing to a queer and feminine divine beyond the exterior, identity-defining gaze of the ever-present 'hungry observation of the Watchers,'[2] who hold its nameless protagonist prisoner throughout the narrative.

For Carrington, as with many surrealists, the figure of the doll, mannequin or automaton was – and is – of recurring interest and reference in their work. Carrington, for example, is known for her use of the mannequin in her paintings, often portraying herself as one or with a mask that resembles the features of her own face. She did so to convey not only her criticism of the relationship of between notions of the modern female with dependency and submission, but of the relationship between the male gaze and female representation in the broader surrealist movement. Simone de Beauvoir famously wrote in The Second Sex that André Breton 'never talks about Woman as Subject,'[3] and it is clear a large volume of surrealism attests to this fact.

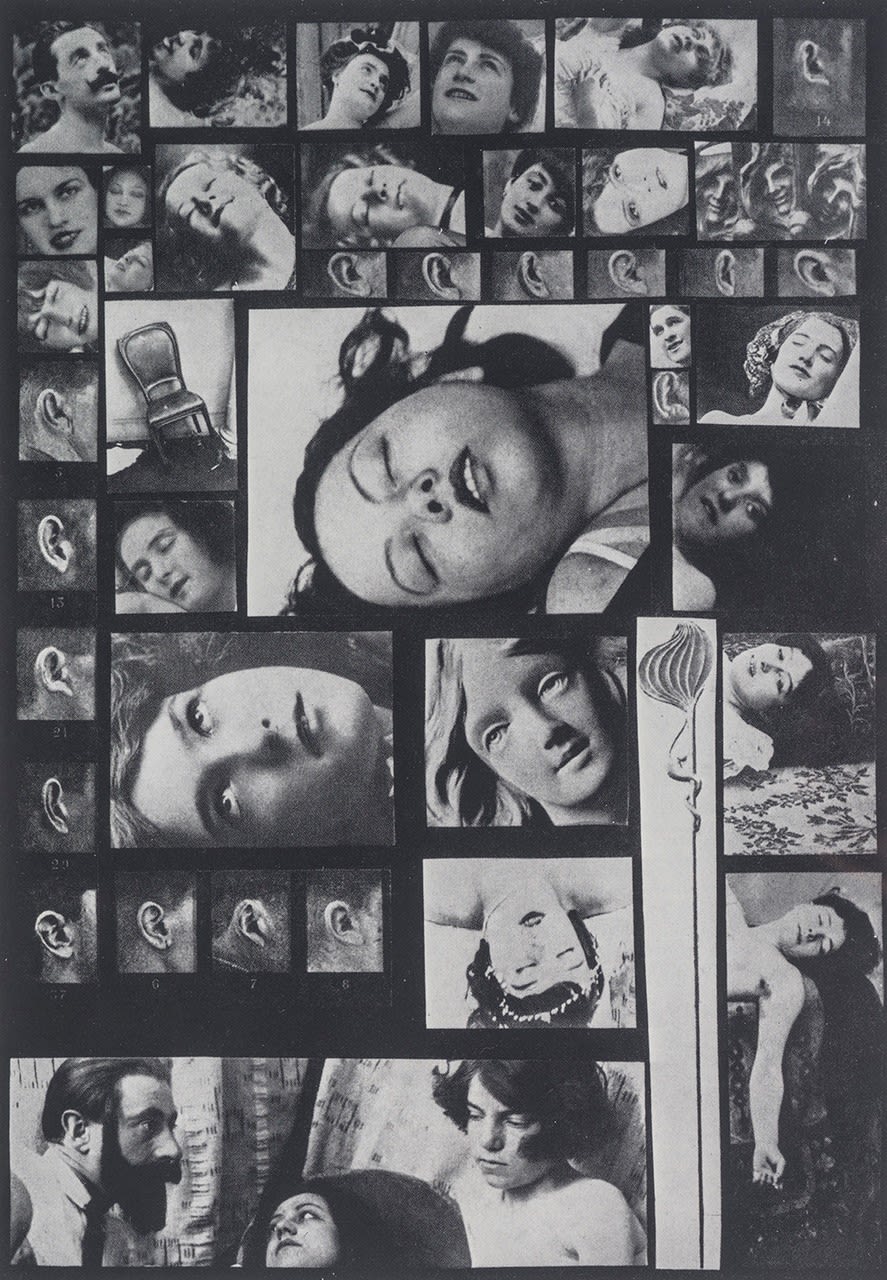

Salvador Dalí’s The Phenomenon of Ecstasy (1933), is a classic case in point, an arresting photo-montage that places at its centre an archetypal image of the femme-enfant – peaceful, angelic, suggestive. Below her image, Dalí places a photo of a marble statue bearing a similar blissful expression, allowing the viewer to gratuitously compare the ecstatic women to that of an inert grey object. Her passiveness is made pure, virginal and innocent through crude association, inviting the viewer to gaze within catatonic intensity and her banal sexualized expression. I’m inclined to name this form of surrealism ‘softcore’ for its not-so-unconscious titillating of masculine desire through the predominance of Lolita-style aesthetics and emphasis on principles of sensual beauty.

Salvador Dalí, The Phenomenon of Ecstasy (1933)

Softcore surrealism therefore hinges on the conflation of childhood, sexuality, femininity and objectification. It is a pervasive form of surrealism which many artists can be charged with reinforcing and exploiting through their use of insidiously erotic female and doll-like imagery (see Dalí, Man Ray, Breton, Delvaux, et al.) and which artists such as Carrington, Dorothea Tanning and Hans Bellmer have challenged in their work – often by means of subverting the very same tropes that have been used to establish them. For me, recent paintings by Rachel Hobkirk, such as those included in this exhibition, Baby Talk, speak to this history of surrealism, the male gaze and its subversion, of course amongst many other things. They do so however through an inarguably contemporary perspective, one which embeds and critiques the fetishised figure of the docile surrealist puppet within modern forms of advertising which use the attention-grabbing power of ‘cuteness’ to encourage consumption or one-dimensional representations of women and their role in society, particularly when allied to sexualised imagery and the commodification of our nostalgia for adolescence.

The smooth 'wet' surface of Hobkirk’s paintings, in harmony with their brightly saturated colours (a glow intensified through layers of underpainting in oil) and airbrush-quality are certainly evocative of screen-based advertising – a quality brought into sharp focus by her own suggestions of photo-montage, now evocative of quotidian split-screen imagery that is part-internet pop up, part-deliberate and obsessive information overload. Dolls are variously zoomed and cropped, showcasing the more uneasy features of their design (in this case, Tiny Tears, the most popular doll of the 1950s), such as tropophobia-inducing hairlines, lascivious pink lips, circular anal-like feeding-holes in the mouth and rolling intoxicated eyelids, the result of the ‘sleepy eye’ innovation which led to doll’s closing their eyes when laid horizontal.

Gillian Wearing, Lily Cole (2009)

There is a provocation in focusing on these palpable elements, sharpened by their rendition as hyper-smooth surfaces that demonstrate a form of reality as representation. There is continuity, for instance, between Hobkirk’s glamorous yet alienated dolls – beautifully preserved and well-dressed, but isolated with a larger than human silence – and Gillian Wearing’s 2009 portrait series of supermodel Lily Cole. Wearing a porcelain mask of her own face, the supposed pinnacle of beauty as a childlike doll is undermined by a haunting sense of the uncanny – a troubling interplay and failure of distinctions between the animate, inanimate and erotic. The cute and the sinister. Attractive and repulsive. Beautiful and grotesque.

Indeed, the characters of Baby Talk exist somewhere between strangely despondent and vacuous symbols of rampant consumer culture, outdated feminine and maternal domesticity, and on the other, as autonomous and charged psycho-sexual beings. They are playful but not sugar-coated, ambiguous but not lost. Alluring, but for what purpose? Together they softly subvert the passive and diminutive framework of softcore surrealism, borrowing in equal measure from contemporary popular culture’s fear of hysterical, paranormal dolls and its increasing fetishisation and aestheticisation of youth, innocence and glamour, particularly seen online. Staged and photographed in the studio, the figures in Baby Talk can themselves be seen as a style of vexed portraiture. The question that we must ask is: who or what is behind the mask? For as Carrington’s goddess continues in her enigmatic parable, 'These mannequins can become animated according to the choice of the individual creature. He or she may have as many mannequins as they please.'[4]

[1] Leonora Carrington, The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington (St Louis: Dorothy, 2017).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (London: Johnathan Cape, 1956).

[4] Carrington.

Tarmac Press, Herne Bay

Catalogue Essay

2023

Brooke Bennington, London

Exhibition Text

2023

Freelands Foundation, London

Catalogue Essay

2023

superzoom, Paris

Exhibition Text

2023

Lichen Books, London

Catalogue Essay

2022

Tennis Elbow, New York

Exhibition Text

2022

émergent, London

Interview

2022

Guts Gallery, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Kupfer Projects, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Collective Ending, London

Catalogue Essay

2021

L21 Gallery S’Escorxador, Palma De Mallorca

Exhibition Text

2021

TJ Boulting, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Quench Gallery, Margate

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Foolscap Editions, London

Catalogue Essay

2020

Gentrified Underground, Zurich

Catalogue Essay

2020

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2019

Kronos Publishing, London

Editor

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Editor

2019

William Bennington Gallery, London

Catalogue Essay

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Catalogue Essay

2018

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2018

Limbo Limbo, London

Exhibition Text

2017

Saatchi Art & Music Magazine, London

Review

2017

B.A.E.S., London

Exhibition Text

2016