Exhibition Text

Natalia Gonzales Martin & Davinia-Ann Robinson: I Am Unsure As If It Is Still Alive

Quench Gallery, London

Written on the occation of I Am Unsure If It Is Still Alive, a duo-exhibition of new work by Natalia Gonzales Martin and Davinia-Ann Robinson at Quench Gallery in Margate (17 April — 2 May 2021), the inaugral exhibition of the new project space launched by artists Lindsey Mendick and Guy Oliver.

The exhibition text focused on an exploration of the soul found in both artists’ work. Focusing on the contrasts between transcendence in the work of Gonzales Martin and immanence in Robinson.

Extract —

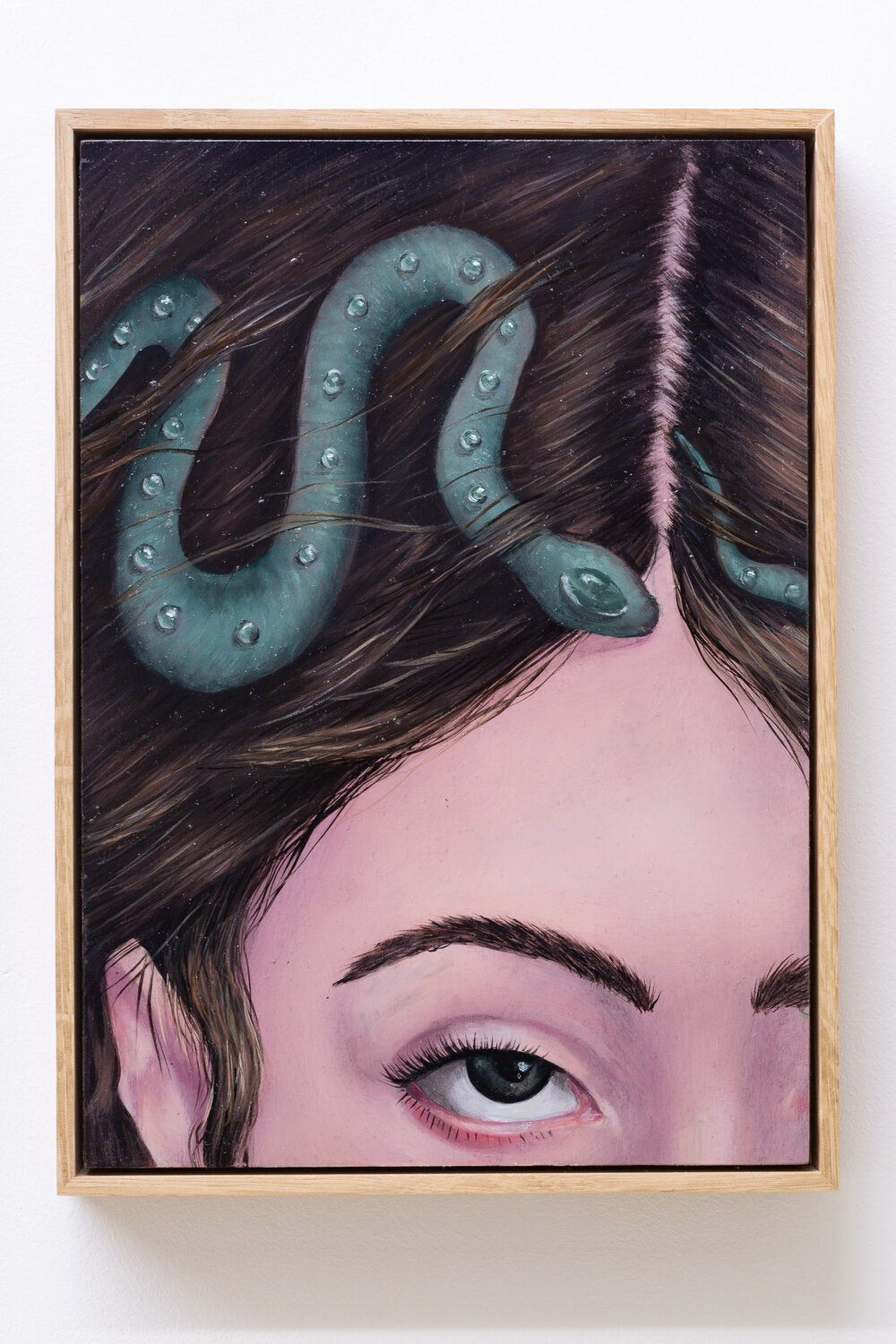

“Heraclitus wrote that, “For souls it is death to become water, and for water death to become earth. Water comes intoexistence out of earth, and soul out of water.” Conceiving the soul as a living memory conterminous with all life, a series ofparadoxes are presented to us. I Am Unsure As To If It Is Still Alive does not seek to explain these paradoxes—betweenabsence and presence, resilience and entropy—rather to reveal them, to confess or disclose a mutual vulnerability. Gonzales evokes the Sacrament of Penance in secular icons that are nothing if not cathartic: the inscription of religiousand cultural heritage on one’s physical body and moral codes. Robinson, in contrast, sublimates and affirms the corporealsoul with that of earth and landscape, confiding her experiences as a body of colour dwelling in colonial environments.Both are charged with the rush of time—permeated by ancient entities or encounters of the past—yet resist accumulationor ownership of the future.

For Gonzales, this antimony is felt in the proximity of ecstasy and dysphoria, captured in the weeping visage of Mary—a symbol of special significance for Catholics: she cries not only over the sins of the world, but also over the pain she endured in her earthly life—as with her references to the myth of Narcissus, in which a reflective stare is elided for ambiguous sensuality, subtly negating the classical dwelling-place of souls in ancient Europe—saiwaz, meaning “from the lake”—for a quiet and serene enchantment. Here, the transcendent and corporeal are mutually constituted—mirrored inthe water, so to speak. Conversely, fragments of Robinson’s body are directly entangled in the process: pigmented thumbs, ears and hands. Embedded in soil drawn from sites of personal distress, they intermingle with the surrounding terrain in reciprocal penetration and intimacy. No less, shards of a softly spoken voice share their syntax with a body of earth and rock: words rupture and desiccate, giving way to faults in the aural landscape.

Composed of golden jewellery, small green plants, hair, soil, and water, Robinson’s works materialise physically that which is formally represented in Gonzales. For the former, these express the enforced dislocation and dissociation of bodies of colour with their natural environment, to which environmental feminist Astrida Neimanis writes, “we must urgently pay attention to how bodies and places respond to our weather-worlds”—and to which we might say for Gonzales, applies equally to the netherworlds of inherited faith, tradition and religious iconography. In each case—it would appear—a soul cannot be extracted from its history, its symbolic or material landscape is a living archive and its scars a shared memory. Despite this common depth and spiritual agency, formal differences remain: the libidinal mysticism of Gonzales juxtaposing the eerie ‘presencing’ of Robinson. These differences are not only complementary but essential, for as Neimanis does not forget to underscore, “not all bodies weather the same”.”

︎︎︎

︎︎︎